“Europe has done a terrific job on many fronts, but it lags far behind the U.S. in terms of innovation, particularly in technology and AI. If it does not address capital markets integration, regulation, and investment incentives, that gap will grow wider.”

— Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan Chase, April 2024 Shareholder Letter

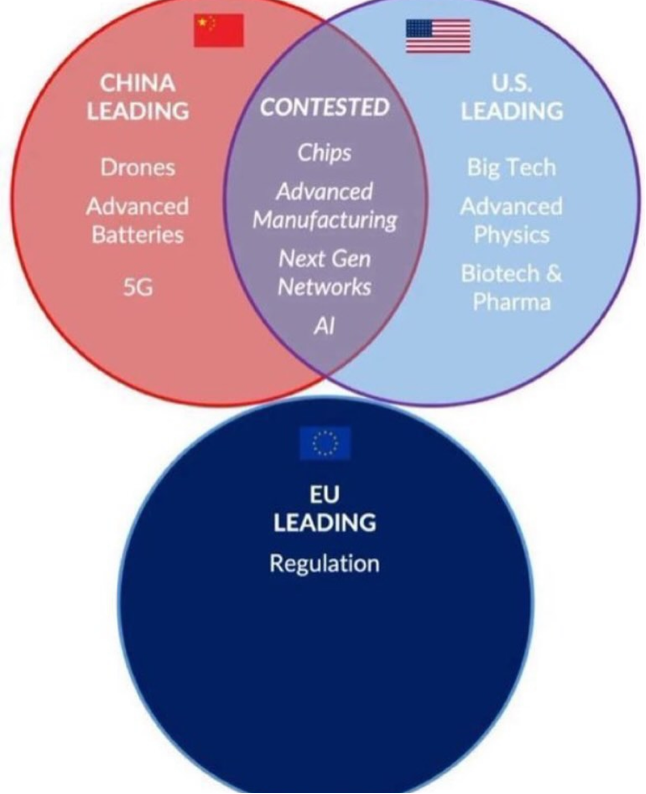

Unfortunately, there’s a degree of truth with the above – it reminds me of the old adage – “America innovates, China duplicates and Europe regulates.” This is something that has been top of mind for me for a while. Every time there seems to be a major trend, especially within tech and/or tech-enabled sectors, both the UK + Europe are always late to the race, whilst we sit and watch the USA and China battle it out to become leaders. Even smaller countries like Taiwan have specialised in semiconductor manufacturing.

Nvidia alone is worth more than the FTSE 100 combined. Apple is worth more than the CAC 40. Combined. And Microsoft is worth more than the Dax 30. Combined. This begs the question – why does Europe, a region with 450+ million people, world class universities, and innovative startups have so few dominant tech companies?

This post unpacks how a mix of risk aversion, fragmented markets, soft capital, and overzealous regulation quietly eroded Europe’s shot at tech dominance and what (if anything) can still be done.

The Scale of the Problem

The numbers tell a stark story about Europe's tech deficit. As of November 2024, Apple leads global tech companies with a market capitalisation of $3.6 trillion, while ASML, Europe's largest public tech company by market cap, is valued at $233.9 billion—less than 7% of Apple's value.

This gulf illustrates the fundamental challenge: Europe simply doesn't produce tech companies that scale to American proportions. The disparity becomes even more pronounced when examining the broader landscape. At the end of 2024, 62 US corporations made it into the list of the world's highest-valued companies, with nine of the ten most expensive companies headquartered in the USA. Meanwhile, European companies are currently not making it into the top tier of global market leaders. While Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon have market capitalisations above or close to $2 trillion, the most valuable public company from Europe barely reaches a quarter of a trillion dollars. The "scaling cliff" becomes evident when examining unicorn creation rates. According to Sifted & TechCrunch, in 2024, 60 US startups became unicorns compared to just 13 European startups that hit billion-dollar valuations—a nearly 5:1 ratio despite Europe's comparable population and economic size. Even more telling, Silicon Valley alone is home to 63 unicorn companies, nearly five times the number that all of Europe produced in its best year. This suggests that European startups face systematic barriers that prevent them from achieving the exponential growth that characterises American tech success stories.

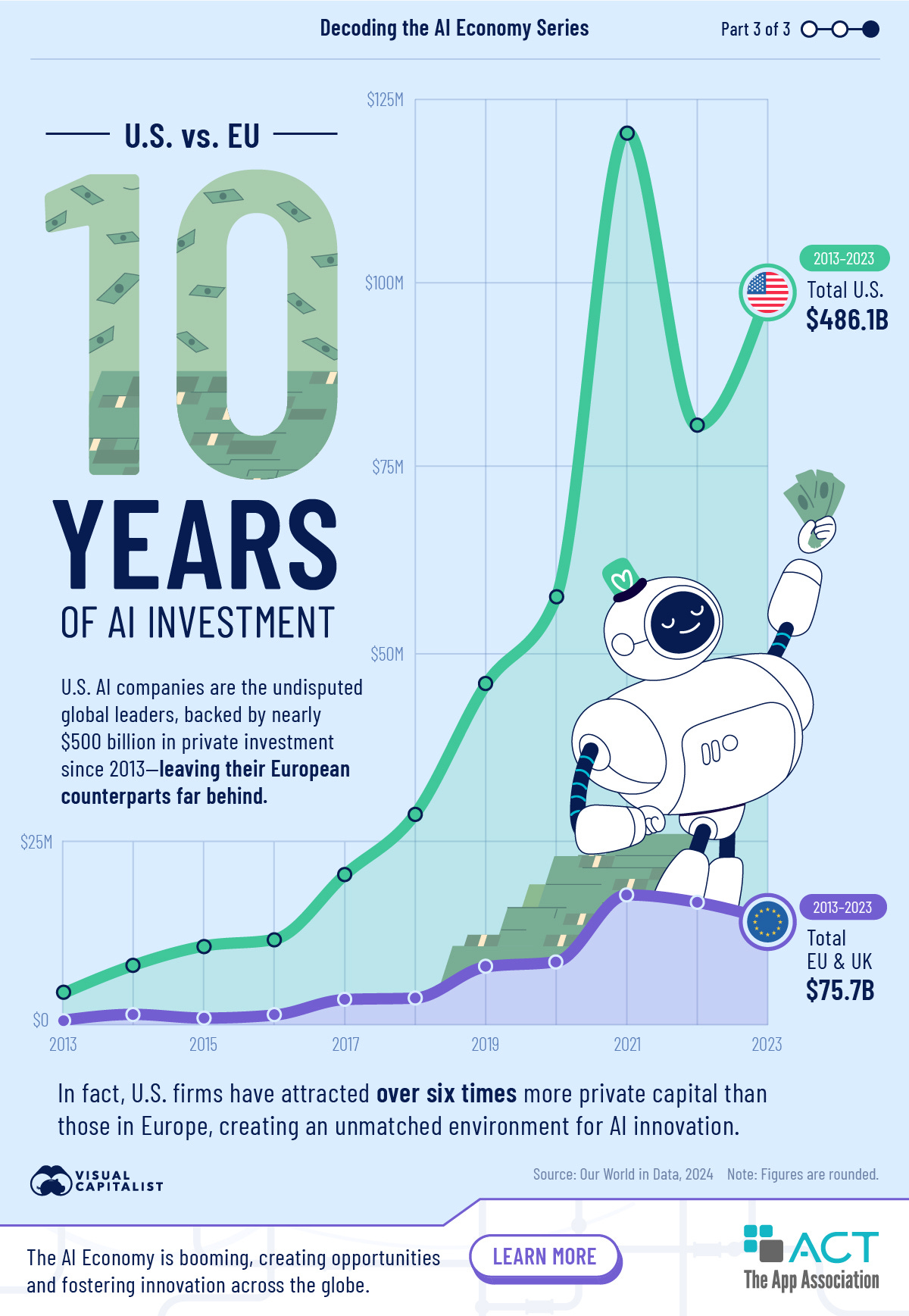

The artificial intelligence (AI) sector highlights a significant scaling disadvantage for Europe in comparison to the United States. Between 2013 and 2023, U.S. and European AI companies collectively attracted nearly $562 billion in funding; however, U.S. firms secured more than six times the amount of private capital compared to their European counterparts. This disparity creates an environment that fosters unparalleled innovation in AI within the U.S.

Recent statistics reveal an even starker contrast. In 2024, private investment in AI-related sectors reached approximately €292 billion in the U.S., €88 billion in China, and only €43 billion in the European Union (EU). This indicates that Europe captured less than 15% of the AI investment flowing to the United States, despite having a similar population size and economic output.

From 2013 to 2024, the United States raised nearly half a trillion dollars in private investment for AI, while the UK—Europe's largest AI investor—accrued only $28 billion. This 17:1 ratio in investment underscores the challenges European companies face in competing within a sector that many experts believe will define the technological landscape of the next decade.

In response to this investment gap, the EU has introduced initiatives such as InvestAI, aiming to mobilize €200 billion for AI investment, which includes a dedicated European fund of €20 billion for AI gigafactories. However, these efforts are viewed as a means to catch up in a race where the United States has already established a significant lead through its private market mechanisms, which the European financial system struggles to replicate.

The Structural Barriers

Europe's tech struggles aren't due to a lack of talent or ideas as we know, they stem from fundamental structural impediments that make scaling extraordinarily difficult. The continent's greatest strength as a diverse, democratic union simultaneously becomes its greatest weakness in the winner-take-all world of technology.

The European market, while large in aggregate, remains stubbornly fragmented across regulatory, cultural, and operational lines. A startup in Berlin faces 27 different regulatory frameworks to reach the full European market, compared to a San Francisco company that can scale across all 50 US states under a single federal structure. This fragmentation manifests in practical ways: different privacy laws, varying tax codes, disparate payment systems, and conflicting employment regulations. A company building a fintech app must navigate not just different languages and currencies, but entirely different banking regulations in Germany versus Italy versus France.

European capital markets reflect a fundamentally different philosophy toward risk and failure. The continent's financial system remains dominated by banks rather than venture capital, with traditional institutions preferring steady returns over exponential growth bets. Pension funds and institutional investors face regulatory restrictions that limit their ability to invest in high-risk, high-reward startups. More critically, European bankruptcy laws and social attitudes toward business failure create a culture where entrepreneurs often get only one chance to build a company, unlike Silicon Valley's "fail fast, fail often" mentality.

Despite the UK ranking third globally in AI funding with $4 billion invested in 2024, and Germany and France each contributing over $1 billion, Europe continues to lose its best technical talent to Silicon Valley. The brain drain operates on multiple levels: stock option taxation in many European countries makes equity compensation far less attractive than in the US, limiting startups' ability to attract top talent with upside potential. Additionally, the sheer concentration of successful tech companies in Silicon Valley creates a gravitational pull—ambitious engineers and product managers migrate to where the biggest opportunities and highest compensation packages exist. There seems to be a problem, particularly in the UK [and maybe Europe too] that our best and brightest graduates get lured into jobs in banking & finance like investment banking, private equity, hedge funds, asset management and equity research.

The Regulatory Straightjacket

European policymakers have emerged as leaders in global digital regulation, crafting an extensive set of laws aimed at addressing the excesses of Big Tech. These regulations, although rooted in commendable goals such as protecting privacy, promoting fair competition, and enhancing democratic processes, have collectively created an environment that is often seen as stifling innovation. As a result, European tech companies increasingly encounter significant challenges when it comes to scaling.

GDPR and Privacy Regulations: A Double-Edged Sword

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into effect in 2018, has fundamentally transformed how businesses manage personal data. A study examining 400 e-commerce companies indicated that GDPR compliance compelled firms to adopt “less integrated technologies.” This is due to the fact that prior efficiency-driven, highly integrated systems became potential legal liabilities. Consequently, the competitive advantage appears to reside more in the utilization of simpler technology stacks, which contrasts sharply with the innovation-driven ethos of Silicon Valley. The burden of compliance extends beyond just technology; startups must secure legal expertise from their inception, diverting critical resources away from product development toward regulatory adherence. Unlike American companies, which can move swiftly and seek forgiveness for missteps, European startups face the necessity of embedding privacy considerations into their products from the outset. This requirement tends to slow their time-to-market and escalate development costs.

Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act: Intentions vs. Impact

As of February 2024, the Digital Services Act (DSA) applies to all platforms, imposing stricter regulations on Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) that serve over 45 million users within the EU. Critics have suggested that Europe should pause new regulations to properly evaluate the long-term impacts of existing laws like the GDPR, DSA, Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the forthcoming AI Act. This regulatory framework has created a challenging environment for companies striving to keep up. The DMA specifically targets “gatekeepers,” primarily affecting major U.S. tech firms such as Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, and Meta. Although these regulations aim to create a level playing field, they introduce further complications. European startups must now not only compete with well-capitalized American firms but also tackle the burden of operating under stricter regulatory constraints. The EU's Data Act, adopted in November 2023, adds another significant layer of complexity to data, privacy, and intellectual property regulation. Such developments have revealed the difficulties even the European Commission faces in adhering to its own data protection regulations, underscoring the challenges of navigating an intricate regulatory landscape.

This environment tends to favour larger companies with specialized compliance teams, creating obstacles for agile startups that need to innovate quickly. For European entrepreneurs, the multitude of overlapping regulations can feel overwhelming, even for those within seasoned legal departments.

European Success Stories (And Why They’re Outliers) in a Challenging Landscape

Despite the regulatory headwinds, Europe has produced notable tech champions that underscore the continent's potential. Analyzing these success stories highlights what is achievable, while also illustrating why they are exceptions rather than the norm.

SAP: A Leader in Enterprise Software

SAP has recently surpassed ASML to become Europe’s most valuable publicly traded company, boasting a market cap of €313 billion. This achievement reflects the growing demand for cloud computing and software solutions. SAP's remarkable growth can be attributed to several unique factors that pose challenges for other European firms. Firstly, SAP entered the enterprise software market at an early stage, allowing it to establish significant network effects and switching costs that create lasting competitive advantages. Secondly, its familiarity with the fragmented European market positions it favourably, as large enterprises often seek solutions that can operate across multiple jurisdictions. Lastly, the business-to-business (B2B) software sector functions differently from consumer tech, with a greater emphasis on relationship-building and long-term contracts rather than rapid viral growth.

ASML: A Specialized Hardware Leader

Despite experiencing a significant decline of over €60 billion in market capitalization following revised growth guidance, ASML remains a pivotal player in European tech hardware. The Dutch company has carved out a niche by specializing in advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment, solidifying its status as a critical supplier in the global market. ASML's remarkable success is underpinned by an exceptional foundation that few other European companies can replicate: an extreme technical specialization within the semiconductor manufacturing sector, characterized by significant barriers to entry. The company’s state-of-the-art extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines are crucial for fabricating the most advanced semiconductors, particularly those used in cutting-edge applications such as artificial intelligence, high-performance computing, and 5G technology. This specialization has effectively created a natural monopoly for ASML, as its EUV machines are essential for major chip manufacturers like Intel, TSMC, and Samsung, thereby transcending traditional scaling challenges that confront many other industries. Furthermore, ASML’s hardware-centric business model is significantly bolstered by Europe’s robust engineering tradition, which emphasizes precision, innovation, and long-term strategic planning. This approach enables ASML to navigate the complexities of a sector that demands substantial investments in research and development over extended periods, often involving decades before products reach the market. As a result, these qualities not only foster innovation but also serve as competitive advantages, positioning ASML at the forefront of the semiconductor industry in a global landscape that continuously evolves.

Spotify: Leveraging First-Mover Advantage in Digital Media

Spotify has recently marked its first full year of profitability, showcasing a 12% year-over-year increase in monthly active users, now reaching 675 million. This achievement highlights the capability of European startups to attain the prestigious unicorn status, demonstrating that these companies can effectively establish global consumer platforms. The success of Spotify can largely be attributed to its early identification of a market opportunity in legal music streaming, a space that American competitors were slow to recognize. Several favourable conditions contributed to Spotify's growth. It launched during a time when the music industry was seeking alternatives to piracy, which allowed it to gain traction. Initially, the company faced limited competition from established tech giants that were focused on different areas, enabling it to carve out its niche. Additionally, by fostering crucial relationships with record labels before the streaming model became widely profitable, Spotify secured its foothold in the industry. A significant aspect of Spotify's strategy was its content licensing model, which meant that expanding into new geographic markets was primarily a matter of negotiation rather than a need to overhaul technical infrastructure. This flexibility allowed the company to scale effectively.

Even the most prominent technology companies in Europe face a fundamental scaling challenge that characterizes the continent's ongoing tech struggles. A notable example is ASML, a leading player in advanced semiconductor manufacturing technology, which saw its market capitalization plummet by more than €60 billion following a reduction in its financial guidance. This incident underscores the fragility that even dominant European tech firms experience in the face of market volatility, which starkly contrasts with the more diversified risk management strategies employed by American tech giants like Apple and Google.

Meanwhile, Spotify, which has recently celebrated achieving profitability for the first time in its history, did so only after enduring over a decade of financial losses. This lengthy timeline poses significant challenges for European investors, who historically have been less tolerant of prolonged periods without returns compared to their counterparts in the U.S.

These success stories serve to illuminate a critical gap in Europe's tech landscape: none of these companies have emerged from a venture capital ecosystem that is so pivotal to the successes often seen in Silicon Valley. For instance, while SAP expanded organically through enterprise sales and ASML's growth was fuelled by decades of intensive research and development partnerships, Spotify's rise relied heavily on innovative content licensing agreements rather than venture-backed startups. This pattern indicates that while Europe excels at optimizing existing systems, it often struggles to create disruptive innovations—an essential factor in industries where value creation is driven by transformative ideas and technologies.

Cultural and Mindset Factors

“There is no shortage of talent in Europe. There is a shortage of ambition, funding, and risk tolerance.”

— Taavet Hinrikus, co-founder of Wise (TransferWise)

One thing I find really fascinating in this discussion is the WHY.

It seems to mainly be a cultural thing. Whilst the US has the ‘American Dream’ culture, starting a new business, competing, and winning the game. The EU + UK can more often look down on this idea as selfish and greedy, and are less prone to start new businesses and attempt to take market share from them as well. It’s one thing that has driven the idea in my head that culture is more important than Policy. Culture IS a policy in itself. It’s one of the most difficult things to navigate when economists are studying things, as its much harder to measure than raw numbers.

The barriers to achieving tech dominance in Europe are not primarily regulatory or financial; instead, they are deeply rooted in cultural attitudes. These mindset differences are reflected in myriad decisions that collectively hinder the growth of large tech companies, despite the availability of talent and capital. I’ll use the examples of 2 comments on the Financial Times on the same post about lack of tech companies in Europe, one of which is a Cambridge PhD founder in his mid-late 20s and the other one I’m assuming works at an investment bank or venture capital firm since he knows how the fundraising process works.

The Risk Aversion Paradox

A fundamental cultural divide exists in how different societies perceive risk and reward, especially within European capital markets. The Draghi report underscores the necessity for Europe to concentrate on closing the innovation gap with the United States and China, particularly in advanced technologies. However, this ambition faces obstacles due to entrenched attitudes toward investment risk. For instance, a young founder in Cambridge points out that substantial funds in pension schemes remain undeployed for innovative, high-risk ventures, as they are often redirected towards safer investments like new construction projects in the southeast of England.

This pervasive risk aversion generates misguided incentives throughout the investment landscape. The UK's Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS), which was intended to stimulate startup investment, can, paradoxically, dissuade it. According to the same founder, investors are often motivated to invest in low-risk startups not for the potential of enormous returns but to take advantage of tax rebates on their income or capital gains. When tax incentives dominate investment decisions, the focus shifts toward safety instead of pursuing exponential growth potential.

At the institutional level, concerning trends are also evident. As the Cambridge founder notes, interactions with established firms often reveal a lack of understanding of venture capital principles. For example, one partner from an established firm discussed a £120-150k investment size for a deep tech startup without grasping that successful funds generally rely on concentrated investments in companies with significant upside potential, rather than a diversified portfolio of safer bets.

The Academic-Industry Cultural Divide

In Europe, there is a noticeable cultural barrier that discourages entrepreneurship, particularly among highly educated individuals. The Cambridge founder articulates this issue by stating that many Europeans appear averse to pursuing profitable careers, often viewing industry as less prestigious compared to academia. This cultural sentiment leads to a brain drain, where Europe's most talented researchers frequently do not consider commercializing their innovations.

This divide also influences career trajectories in ways that may seem illogical to observers from the United States. An anonymous founder comments that many graduates from top universities often choose careers in hedge funds, where they can earn significantly higher salaries, rather than venturing into startups. This trend reinforces a cycle where entrepreneurship is seen as less legitimate or desirable compared to more traditional finance careers.

The Pace of Business Culture

European business culture tends to prioritize consensus and employee protection over speed and flexibility. The differences become especially clear when examining timelines for initiating new ventures. For instance, a founder compares processes in the US and UK: in the US, an employee can leave their company and start a new venture within weeks, while in the UK, employees may face lengthy notice periods and non-compete clauses extending the timeline.

This disparity in pace permeates the startup lifecycle as well. When recruiting, delays in onboarding talent can stall progress significantly. A US startup might bring on a former colleague in just a couple of weeks, whereas a UK counterpart may have to wait several months due to legal constraints, which hampers rapid iteration and adjustment.

Government Short-Termism

The Draghi report advocates for a comprehensive, centrally-coordinated industrial policy to advance clean technology. However, European political systems often struggle with the long-term vision required for developing deep tech. As expressed by a Cambridge founder, the lack of commitment to high-capital, long-term projects is evident in recent governmental decisions to cut funding for essential research facilities. This trend negatively impacts the entire ecosystem of innovation, as the diminished support for foundational research leads to fewer groundbreaking discoveries.

The cycle of short-term thinking perpetuates a harmful situation: without governmental backing for basic research, universities produce fewer high-impact innovations. This, in turn, restricts the number of high-growth startups emerging from these advancements. A lack of successful startups creates the notion that government investment in research is not yielding tangible benefits, making it easier for further cuts to be justified in the future.

The Exit Expectation Gap

The cumulative effects of these cultural and mindset factors create significant challenges, particularly regarding expectations around exits for startups. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for stakeholders aiming to foster a healthier ecosystem for innovation and entrepreneurial growth in Europe.

The Path Forward: Integrating the Draghi-Letta Vision

“Europe has done a terrific job on many fronts, but it lags far behind the U.S. in terms of innovation, particularly in technology and AI. If it does not address capital markets integration, regulation, and investment incentives, that gap will grow wider.”

— Jamie Dimon, Current CEO of JPMorgan Chase

In 2024, two landmark reports were published, providing Europe with a comprehensive roadmap aimed at enhancing its tech competitiveness. These documents not only articulate the significant ambition required to revitalize Europe’s tech landscape but also highlight the political hurdles that complicate their execution.

According to the ambitious Draghi Report, Europe must escalate its innovation initiatives to effectively bridge the considerable gap with the United States and China, necessitating an annual investment of between €750 billion and €800 billion—representing around 4-5% of the EU's Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This recommended shift underscores a transformative approach to funding innovation within Europe. The report explicitly calls for strategic collective efforts to narrow this innovation gap, with a specific emphasis on advanced technologies and addressing three pivotal challenges: rectifying the innovation gap with the U.S., achieving a harmonious balance between decarbonization and competitiveness, and enhancing economic security through reduced dependencies on external sources.

The magnitude of this investment requirement starkly contrasts with Europe’s current funding efforts. The projected €750-800 billion annual figure greatly exceeds current EU innovation expenditures and would necessitate either substantial increases in contributions from member states or a comprehensive restructuring of the EU budget. Such a reorganization might involve significant alterations to longstanding agricultural and cohesion subsidies to create a financial framework more focused on innovation and skill development—as advocated by Draghi. However, this proposal is politically contentious, as it would demand the dismantling of decades of carefully negotiated fiscal agreements.

In a complementary effort, Enrico Letta's report, “Much More than a Market,” published on April 17, 2024, proposes sweeping reforms designed to empower the EU Single Market. The report highlights the necessity for a collective initiative to redefine the Single Market's scope and function, emphasizing themes that aim to support a fair green and digital transition, bolster EU security, and foster job creation and ease of business operations. The Letta report takes a direct approach to addressing Europe’s fragmentation, proposing what could effectively be dubbed a "Digital Single Market 2.0." This initiative seeks to establish genuinely unified regulatory and operational frameworks across member states. Among its recommendations are empowering research infrastructures, developing a robust European technological landscape, creating a European Knowledge Commons, eliminating barriers to knowledge sharing, and fostering public-private partnerships.

Both reports converge on a fundamental insight regarding Europe's tech landscape: the continent's most significant disadvantage isn't merely regulatory complexity or cultural attitudes, but rather the acute lack of deep capital markets capable of financing exponential growth. The Draghi report includes a goal of creating a Capital Markets Union—essentially an initiative to cultivate a European equivalent to the progressive venture capital and public equity markets prominent in the U.S. Letta also emphasizes the pivotal role of private capital, framing it as a necessary step toward establishing a more inclusive and efficient financing framework. This presents a considerable challenge to the existing European financial culture; for example, pension funds and insurance companies must significantly augment their appetite for risk, while retail investors need to adopt equity ownership habits comparable to those prevalent in American markets.

The Centre for European Reform notes that while Letta's report offers a range of sensible proposals aimed at strengthening the EU's economy, it ultimately leaves member states to prioritize and navigate the inevitable trade-offs involved in implementation. This aspect emphasizes a fundamental challenge: both reports call for member states to potentially sacrifice short-term interests for the sake of long-term collective benefits.

The Draghi-Letta vision essentially advocates for the establishment of a “United States of Europe” in economic terms—featuring unified markets, integrated capital flows, and a coordinated industrial policy framework. To achieve this, the Draghi report lays out three major initiatives: a concerted effort across member states to enhance the EU's business environment, an investment-centric approach to innovation funding, and policies that foster collaboration among private and public sectors to drive technological advancement.

This comprehensive approach underscores the urgency and significance of reshaping Europe’s economic landscape to meet the challenges of the future.

Conclusion: The European Paradox

Europe's tech deficit is not a reflection of a lack of talent, innovation, or ambition; rather, it is the result of a continent that has chosen a unique vision for society. The data clearly illustrates this: American tech companies consistently achieve market capitalizations far surpassing their European peers, Silicon Valley produces unicorns at a rate five times greater than Europe, and European startups navigate systematic barriers from fragmented markets, risk-averse capital, and complex regulations—challenges that American companies often do not face.

However, framing this as a "failure" overlooks the profound truth revealed by examining Europe’s structural barriers and cultural distinctions. The very social frameworks that present hurdles to the emergence of trillion-dollar tech companies simultaneously cultivate societies with robust worker protections, comprehensive social safety nets, and democratic institutions that place citizen welfare above corporate growth. Those lengthy three-month notice periods may slow the pace of hiring for European startups, but they also provide a level of job security that American workers often lack. The privacy regulations that create obstacles for European tech development also safeguard citizens against the pervasive reach of surveillance capitalism that is increasingly scrutinized in the United States.

The Trade-Offs Are Real

The journeys of European founders seeking to build their companies highlight the tangible costs of these trade-offs. When a Cambridge PhD must endure months for non-compete clauses to lapse, when institutional investors offer £120,000 tickets for deep tech startups, when the brightest graduates opt for hedge funds over entrepreneurship, these situations are not flaws in the European system; they embody the features of a different social contract.

Europe’s approach to innovation mirrors its core values: consensus over speed, stability over disruption, and collective welfare over individual wealth creation. These principles have birthed some of the world’s most livable societies, yet they inherently challenge the exponential growth often characterized by Silicon Valley success.

The Success Stories Point the Way

ASML, SAP, and Spotify have thrived not by transcending European constraints but by creatively transforming those constraints into competitive advantages. ASML’s patient capital approach aligns perfectly with the demands of hardware industries requiring extensive R&D. SAP excels in fragmented markets due to its multinational expertise. Spotify’s adeptness at content licensing reflects deep-rooted European diplomatic traditions. These companies have successfully embraced their European identity while achieving remarkable success. Oh, and Arm Holdings in the UK too.

The Reform Agenda's Limitations

The Draghi and Letta reports lay out comprehensive reform agendas that could genuinely enhance European competitiveness. Investing €750-800 billion annually in innovation, establishing a true Capital Markets Union, and creating a genuine Digital Single Market could revolutionize Europe’s tech landscape. Yet, executing these reforms demands a level of political will and social consensus that may be elusive.

More critically, these reforms prompt European societies to contemplate a shift toward American norms without fully considering what they might sacrifice. Embracing Silicon Valley-style venture capital markets entails accepting Silicon Valley-style inequality. Adopting a "move fast and break things" mentality risks undermining the institutions that embody "consensus and social protection." The real question lies not in whether these reforms could succeed but in whether Europeans truly desire them.

The Real Choice

Europe is at a pivotal crossroad, facing a genuine choice rather than just a policy dilemma. It can chase American-style tech dominance by adopting American-style capitalism, risk tolerance, and social structures. This path may yield larger tech companies, more unicorns, and heightened GDP growth, but it would also likely usher in greater inequality, diminished worker protections, and reduced democratic oversight over technology.

Alternatively, Europe can embrace the reality that its social model places inherent limits on its ability to generate trillion-dollar tech firms while simultaneously continuing to shine in areas where its core values present competitive advantages: sustainable technology, privacy-preserving innovation, and human-centered design. This path preserves the attributes that make European societies appealing while acknowledging the challenges in winner-take-all tech markets.

The False Binary

The most probable outcome is neither a complete Americanization nor a resigned acceptance of tech mediocrity. Europe will persist in nurturing successful tech companies that embody European values and constraints. It will innovate in areas where regulation becomes a competitive edge—such as sustainability, privacy, and human-centered AI. It will forge businesses prioritizing long-term value creation over mere exponential growth.

While this may not yield the next Apple or Google, it could very well give rise to the next generation of companies that Americans may one day wish they had created. As Silicon Valley confronts growing scrutiny regarding inequality, privacy, and democratic governance, European tech firms’ commitment to sustainable growth and stakeholder value may ultimately prove more resilient than the shareholder-return focus of American tech giants.

Much to agree with on this article. I would add that China certainly innovates at a speed and scale that can be bewildering. In Biotech for instance, Chinas recent rise has been arguably the story of the past 18 months and threatens to undermine US leadership in this critical sector.